| Muskegon Chronicle Grand Haven man knows, fears seiches Sunday, January 30, 2005 By Jeff Alexander |

|

|

|

Beaton |

Bob Beaton said he immediately thought of Lake Michigan when he saw

television footage of the cataclysmic tsunami that killed thousands in South

Asia the day after Christmas.

The Grand Haven resident and longtime surfer has spent the past 25 years collecting information on tidal waves ... actually, Great Lakes tidal waves, known more specifically as seiches. Beaton said he has thousands of newspaper articles on seiches and the devastation caused by the wind-driven storm surges.

A seiche is a storm surge or series of waves caused by high winds, or fast-moving squall lines with intense atmospheric pressure, that cause a lake to slosh back and forth. Seiches have been known to raise water levels on Great Lakes beaches by 10 feet in a matter of minutes.

Over the years, the storm-driven waves have killed dozens of Great Lakes residents, destroyed boats and damaged marinas and other shoreline structures.

"When I saw the tsunami on the news, I thought it looked just like a seiche. It had the same characteristics, but on a much larger scale," Beaton said.

The underwater earthquake that sent a 30-foot high wall of water roaring across the Indian Ocean at 500 mph wiped out entire coastal villages in Indonesia and elsewhere and killed more than 225,000 people.

Seiches have never caused anywhere near that much devastation in the Great Lakes.

Most seiches in

Lake Michigan go unnoticed because they are relatively subtle, causing water

levels on beaches to rise a foot or less. The phenomenon is most common in

Lake Erie, which is not as deep as the other Great Lakes. The shallower the

lake, the bigger the seiche.

|

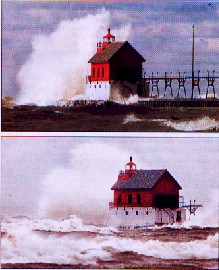

There is a difference between a Great lakes seiche and big waves. These two photos of the Grand Haven lighthouse, taken two weeks apart in October 2001, illustrates the difference between large waves and a seiche accompanied by large waves. Above: large waves pound the lighthouse, but the lake’s water level remains below the top of the concrete breakwater (note the presence of sheet piling on the side of the pier). Below: A seiche that preceded the waves elevated the water level over the top of the breakwater (note how the steel sheet piling is under water during the seiche). Chronicle file photos

|

|

|

"On Lake Erie, it's not uncommon to see a seiche create a storm surge that elevates water levels in Buffalo by 3 feet, and lowers it 3 feet in Toledo, a couple of times per year," said David Schwab, a research oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Great Lakes office in Ann Arbor.

"Often times, in the channels in Buffalo and Toledo harbors, the water levels will drop low enough that boats are sitting on the bottom."

Schwab said there are three different types of Great Lakes seiches:

* A cross-lake seiche driven by winds out of the west or east, which would cause Lake Michigan water levels to rise and fall most noticeably along the coasts of Michigan, Wisconsin and northern Illinois. These are the most subtle, but longest-lasting, Great Lakes seiches; the lake can rock back and forth for as long as nine hours.

* A north-south seiche driven by strong winds out of Canada or the southern United States. This type of seiche would cause water levels to fluctuate at the north and south ends of Lake Michigan, but the event would last two hours or less.

* The most dangerous Great Lakes seiches are those fueled by squall lines with high winds and rapid changes in atmospheric pressure that push down on the lake's surface. Those seiches usually last less than an hour, but can push a huge mound of water across the lake. Upon reaching the shoreline, such seiches can cause water levels to quickly rise several feet; they are often followed by high winds and huge waves.

The National Weather Service broadcasts seiche warnings when conditions are right for such an event. Schwab said beachgoers should keep an eye on the sky when lines of thunderstorms are in the weather forecast.

"If you see a squall line moving across the lake, that's a good indication you should get out of the water," Schwab said. "The danger is that the water may be calm before the squall line comes in, pushing the storm surge ahead of it. The water can rise gradually or quickly."

A seiche that struck Ludington beaches on July 2, 1956, surprised swimmers and anglers on the city pier. The lake was calm before the water level suddenly rose 10 feet and pushed 150 feet past the normal water line on the beach. The rising water swept anglers off the pier and sent sunbathers running for safety as swimmers struggled against the fierce currents.

After the first surge of water, the lake receded 15 feet below the normal water line. Lifeguards on duty at the time feared a repeat of a 1954 seiche that drowned eight people in Chicago. When the lake receded, they ordered everyone out of the lake, according to an article in The Chronicle the next day.

"I figured it would be the same kind of swell that hit Chicago," lifeguard Russ Vorce told the newspaper. "The water receded for 15 minutes, then it rolled back in a big wave. In just 15 seconds the water was waist-high on the breakwater ... all those people trying to reach shore and high ground kept slipping off the breakwater."

Another lifeguard had to jump into the waist-deep water when the second wave toppled the lifeguard tower.

The people who experienced the Ludington tidal wave were lucky. They lived to tell their story of a terrifying encounter with a Great Lakes seiche.

This material is hosted by

www.sandhillcity.com

aquadoc@novagate.com